Still Not Free: Connecting The Dots Of Education Injustice

By Peri Stone-Palmquist | February 13th, 2020

Families come to the Student Advocacy Center of Michigan ready to fight for their education in the face of expulsion, long-term suspension, enrollment denial or a unilateral placement to an online school. The same is happening across the country with Dignity in Schools Campaign members.

Typically, when I share that a 5th grader or 9th grader is being expelled for an entire year with no right to an education and no right to return, most people’s jaws drop. When I explain that 6 students are expelled every school day in Michigan and many, many more are suspended, I hear things like, “What?” “That can’t be.” “I thought education was a right.” “What are they supposed to do?”

I remember having that same reaction when I first met expelled students back in 2000. While I’m no longer shocked by these statistics and struggles — and while I know how long black and brown people have struggled for their education — recent dives into our history have given me pause. I had not stopped to fully appreciate how long and hard this struggle for education has been. I had not fully appreciated the creativity and perseverance of the advocates who came before us all. I had not fully connected the dots from our early days of denying education to formerly enslaved people to today’s struggle to deny education to black and brown youth through expulsion, suspension, the proliferation of virtual schools, school closures and underfunding in majority minority neighborhoods. When I took the moment to pause and reflect, it felt like a punch in the gut and a renewed call to action.

Our history — like our present — is shameful and discriminatory, yet full of persistent and creative fighters.

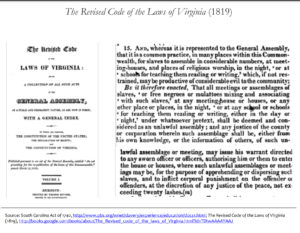

Despite my own studies of history, I was a bit surprised to learn that the United States is the only country known to have had anti-literacy laws. Between 1740 and 1834, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, and Virginia all passed anti-literacy laws. Many of these laws made teaching enslaved Africans to read or write punishable by fines, imprisonment and physical punishments.

Formerly enslaved Africans documented severe punishments for learning to read or write, including amputation. Doc Daniel Dowdy, a slave in Madison County, Georgia, said, “The first time you was caught trying to read or write, you was whipped with a cow-hide, the next time with a cat-o-nine-tails and the third time they cut the first jint offen your forefinger” (“We Slipped and Learned to Read:” Slave Accounts of the Literacy Process, 1830-1865, by Janet Cornelius in the journal Phylon, Vol. 44, No. 3 (3rd Qtr., 1983), pp. 171-186). Other formerly enslaved Africans said they risked beatings and beheadings.

Today, we suspend black boys for “insubordination,” being in the hallway at the wrong time, having a hoodie over their head or a pick in their hair. We assign black boys to understaffed virtual schools when they struggle with their grades or don’t come to school. We send black girls home when their hair color doesn’t conform to white norms. We mace them and arrest them when they try to break up a fight with their brother or raise their voice in the hallway. We ask law enforcement to patrol and enforce minor nonviolent violations of probation, handcuffing children in their schools and leading them out doors to take them to courtrooms full of black children, not in school.

We are still taking away education in 2020.

Before we get too discouraged, we must honor and remember that there can’t be a singular reading of history. History is best interpreted through multiple perspectives, and there has always been an enduring spirit of resistance. Oppressed communities have always fought for their education and to secure their future.

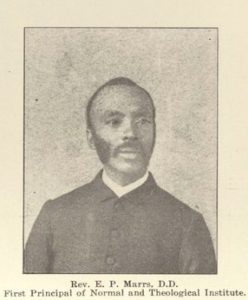

Formerly enslaved Africans report that they taught themselves to read. Elijah P. Marrs said, “I availed myself of every opportunity, daily  I carried my book in my pocket, and every chance that offered would be learning my As, Bs and Cs.” Family also played a key role. Anderson Whitted reported that his father was allowed to use a horse to travel 14 miles to visit his son to reach him to read on biweekly visits. Siblings would pass along what they were taught, sometimes from the children of slave owners. Grandmothers taught Sunday School and other lessons when they could.

I carried my book in my pocket, and every chance that offered would be learning my As, Bs and Cs.” Family also played a key role. Anderson Whitted reported that his father was allowed to use a horse to travel 14 miles to visit his son to reach him to read on biweekly visits. Siblings would pass along what they were taught, sometimes from the children of slave owners. Grandmothers taught Sunday School and other lessons when they could.

And plenty others served as teachers, despite the great risk to their health and life. Enoch Golden was said to confess on his deathbed that he was the cause of death of many a slave because he taught so many to read and write.

Free African-Americans also taught and financed those few schools and classes for black people that did operate in the South (Ervin and Sheer, “A Community of Voices on Education and the African American Experience: A Record of Struggles and Triumphs” 2016).

John Berry Meachum, an African-American pastor and teacher, established the Floating Freedom School in St. Louis after Missouri passed its anti-literacy law in 1847 to circumvent the law.

In this struggle for education, we must always center black and brown voices, but honoring white anti-racist resistors provides some hope and an example of a positive white, anti-racist identity. This is not just the work of the communities who are oppressed. It is very much the responsibility of white allies to support, lift up and stay present. When I read about someone like Margaret Crittendon Douglass, I think about how far we need to be willing to push ourselves. Margaret was a Southern white woman who served one month in jail in 1854 for teaching free black children to read in Norfolk, Virginia. I believe these kinds of examples can be instructive for hopeful and aspiring white allies as we organize to support the work of black and brown parents, students and organizers.

Today, I see resilience and creativity in efforts to fight for education, whether through report cards from black academics or new assessment tools that use a critical-race theoretical framework to understand the strengths our students bring to school each day. Student Advocacy Center’s youth have marched from Detroit to Lansing to show how much their education meant to them. We testified in Lansing. Our advocates have created tools to help districts implement our state’s new discipline laws, overturning zero tolerance, and offered trainings to improve understanding. We keep showing up at those expulsion hearings and working with our parents and students to challenge lengthy time out of school.

I see advocates who are tired and discouraged, too. Even with our very real progress, we continue to face an uphill battle. To be honest, I am sometimes discouraged by this reality. I feel impatient with the slow progress. Our laws offer too little protection and accountability. Our neighborhoods and schools grow ever more segregated. While the mental health needs seem to be growing, funding continues to shrink. And too many cling to tired beliefs, convinced that time out of school is what is necessary to make “schools safe.”

But when I think of the persistence of Elijah P. Marrs, John Berry Meachum and Margaret Crittendon Douglass in the face of such seemingly insurmountable odds, I am inspired to keep fighting. They did not rest and neither can we.

Peri Stone-Palmquist is the Executive DIrector of the Student Advocacy Center of Michigan. The SACoM works collaboratively with underserved students, and their families, to stay in school, realize their rights to a quality public education, grow and experience success.